HAPPY HOGMANAY, WITH THE BROONS

In the small, fictional, Scottish town of Auchenshoogle live a family of eleven, whose exploits have entertained the nation since 1936.

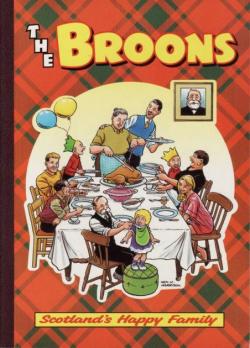

The Broons have, in their own unassuming way, become national treasures, with a comic strip appearing each week in the national newspaper the Sunday Post, and collected biannually at Christmas.

Originally illustrated by the legendary comic artist Dudley Watkins, whose single page stories of an extended working class family were published each week alongside the similarly simple adventures of Oor Wullie, a mischievous young boy and his small gang of friends, these are innocent, heart warming and funny stories of family misunderstandings, or the dangers of hubris, or social climbing gone wrong. Watkins would work on these stories until his death in 1969. The Sunday Post chose to publish reprints for seven years rather than replace him, but since then other artists have stepped into the role, mimicking Watkins’ instantly recognisable style.

DC Thomson have been publishing giants for more than a hundred years. Originating in Dundee, a city of 150,000 people and famed for its historic industries of “jute, jam and journalism”, the DC Thomson empire still sells around 200 million magazines, newspapers and comics a year, including a range of well known kid’s comics. The Sunday Post, a newspaper only sold in Scotland, Northern Ireland and the North of England, at one time had a readership of almost three million. More than half of the population of Scotland purchased the newspaper each week, and so were familiar with the Broons and Oor Wullie cast members.

The publishing industry may have declined, but still the popularity of the characters lives on.

Almost every home in the nation knows of house proud matriarch Maw and her moustached and old fashioned husband Paw. They knew their grown up children, the awkward Hen and handsome Joe, and daughters, the shy Daphne and outgoing Maggie, as well as the younger, bookish Horace, the constantly warring Twins, the youngest of the family, after all this time still known only as the Bairn (the Baby), and Paw’s own aged father, the loveable rogue Granpaw.

The stories have changed over time, but the characters have not. Joe and Hen might once have signed up to go to war against Hitler, but the same characters now have mobile phone problems. The Twins have got no older, the Bairn has never been given a name, Paw might still sometimes go to work in the shipyards, an almost forgotten industry nowadays, and Granpaw is as likely to be confused by social media as he once was with his black and white television. Times change, but the people stay the same. Each week, Paw might accidentally embarrass himself in front of the neighbours, or Hen and Joe might fall out over a girl, or the Bairn might be upset that she can’t find her favourite doll. Each week, their short comic strip is published with the original tagline “Scotland’s happy family, that makes every family happy”. They remain constant and familiar, and there is a reassurance in that. For all their foibles or foolishness, we know people like these characters, and can see ourselves in them.

Growing up in the UK, it was obvious to many people for an extended period of time that the voices heard on the TV and radio, the voices of successful and important people, were often very different from their own. There are a host of regional dialects across these small islands. Take a twenty minute car journey in any direction and you’re likely to find people speaking with different accents or colloquialisms.

The divide has since closed, and regional accents are now commonplace in the media, the old-fashioned “received pronunciation” of news reports of yesteryear has long since fallen out of fashion. Increasingly, many scholars in the subject of language have come to regard Scots as a separate language, related to, but distinct from, English. One that draws words from Gaelic and Scandinavian languages, but with a rhythm and syntax of its very own. For a long time, it was more common to be told that Scots was simply badly formed English. It was improper and impolite, a sign of a lack of education. Scots words were reserved for the Broons and poetry of Robert Burns. The high brown and the low. (Although the much beloved Robert Burns held an ambition to work in the slave trade, so I’ll allow you to make up your own mind as to which is which.)

The Broons has always been unashamedly Scots. Their popularity historically is no doubt related to the fact that for many people, the weekly Broons story was the only time they saw their own words in print. If Maw got angry that the Twins were mawkit ‘ahind the lugs, or Granpaw was a gallus ejit, the reader felt a closer bond, since this was the only time they would likely see these words in print, regardless of how often they might have heard them.

Changes in the way we communicate, where we get our entertainment and information from, and the political make up of the whole of the UK, has transformed the nation in the last few decades. But as the Scotland has gradually become more at ease with itself and the cultural phenomenon known as the “Scottish Cringe” fallen away, the Broons role in popular culture has increased even further. Over the last couple of decades, Scotland has moved from a nation that thought of itself as purveyors of tartan, bagpipes, and sporting failures, to a nation that increasingly thinks of itself in terms of innovation and social justice.

Recognising the interest in all things Broons, DC Thomson moved to regarding the Broon family as a brand. In the last few years, the Broons have moved from a biannual collected edition, to annual. Several cookbooks of traditional Scottish recipes, written in the style of Maw’s own cookery notebooks, have been published. Tour guides have been produced under the Broons’ auspices, as well as guides to Scottish traditions and poetry. There has been a live stage play celebrating the Broon family and their place in Scottish culture, and several albums of traditional Scottish Music - and for anyone unfamiliar with such gems as “The Jeely Piece Song” (which is about trying to catch a sandwich thrown from a high building) or “Ye Cannae Shove Yer Grannie Aff A Bus” (which explains the reasons an elderly relative should not be thrown from public transport. I swear these are true), you’re in for a treat.

There are descendants of Scots in nations across the Earth. Scottish traditions are celebrated on every continent. Whether it's a group of people getting together every 25 January to celebrate to life of Robert Burns by reciting a poem in honour of a big sausage, or the family day out at a Highland Games where burly men compete to see who can throw a tree the furthest, or when men simply use an opportunity to achieve their secret dream of wearing a skirt in public. Traditions, from the ridiculous to the sublime, are shared as a way of remembering where we came from and the ties that bind us. As the saying goes, “we’re a’ Jock Tamson’s bairns”. Sharing the Broons and their homely and charming adventures is another tradition, which I hope you will share in this festive season.

Happy Hogmanay, everyone!

Comments

- Gavin Johnston's blog